From Rebels to Revolutionaries: A Brief History of the Founding of the Fenians and the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland and the United States, March 17, 1858 by Peter Vronsky

Founded in 1858 by former Young Irelander rebels James Stephens in Dublin and John O’Mahony in New York City, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Ireland and the Fenian Brotherhood (FB) in the United States was a predecessor to the twentieth-century IRA. In fact the Fenian insurgents who invaded Canada in 1866 called themselves the Irish Republican Army (IRA)—the first known usage of that appellation.[1] Eventually the IRB became known as the “Fenians” even back home in Ireland and in England.[2] Their goal was the creation of an independent democratically liberal republican Ireland free of the British Crown, a nationalist ambition shaped by a seven century-long conflicted yet symbiotic relationship between the Irish and English peoples which is beyond the scope of all the bandwidth of the entire internet to describe satisfactorily.[3]

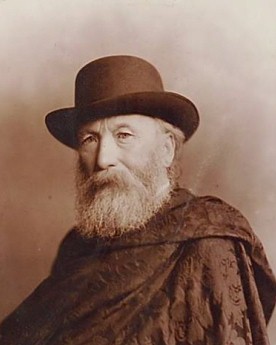

JOHN O'MAHONY: co-founder in New York City of the Fenian Brotherhood. |

After the bloody Irish Rebellion of 1798, for the next fifty years the main thrust of political dissent in Ireland was channelled into peaceful legislative and constitutional reform. The Catholic Daniel O’Connell spearheaded two great political movements one after the other—the emancipation of Catholics and the repeal of the Act of Union. O’Connell’s strategy involved rallying thousands of Irish Catholics in ‘monster meetings’—the largest estimated at 750,000 strong at Royal Hill in August 1843. These huge demonstrations were disciplined and well behaved, which perhaps was even more terrifying to the authorities of that era than small unruly uprisings. In 1828 despite proscriptions on the election of Catholics to Parliament, O’Connell was elected and in 1829, Parliament lifted the remaining legislative vestiges of the Penal Acts with the passage of the Emancipation Act. Now O’Connell would turn his attention to promoting the repeal of the Act of Union through the same strategy and tactics, but this time attempting to bring Protestants into his movement as well.

Parallel to O’Connell’s legislative movement in the wake of the failure of the 1798 Rebellion, there arose a new network of radical secret societies in the tradition of the Defenders: the Ribbonmen. Historians have often dismissed Ribbonism as a “post-United Irishmen-pre-famine” continuation of the Whiteboys and Defenders tradition—a type of peasant self-defence association bordering on a mafia. Tom Garvin suggests that Ribbonism was something more:

These societies developed into regional networks and tended to become politicized, some of them eventually becoming affiliated to quite elaborate all-Ireland organizations. Some were also attracted to politics of a nationalist and quasi-revolutionary kind to further their activities….they served as prototypes for the far better-known separatist Fenian movement of the I860s.[4]

Perhaps more important than what historians think, is what the Fenians might have thought. Garvin quotes Michael Davitt, one of the Fenian founders who attributed the movement’s lineage through a line from Defenderism to Ribbonism. According to Davitt, late Ribbonism was an international proto-political movement which migrated with Irish labourers to Britain and the United States, while Matthew Barlow has described their presence and activities in Canada.[5]

Interest in O’Connell’s popular legislative movement was stopped dead by an unprecedented calamity of holocaust proportions—the Irish Potato Famine of 1845-1849. It impacted most on Catholic peasants who depended upon the potato for subsistence and drove at least 1.5 million predominately Catholic refugees to immigrate and killed another eight hundred thousand to one million by starvation and disease. In 1841 the population of Ireland was 8.2 million. At the current rate of growth it should have reached 9 million easily by 1851. But the census in 1851 showed a surviving population of only 6.5 million.[6]

The famine and the British government’s mismanagement of it to the extent that some characterize it as an act of blatant genocide, radicalized some of O’Connell’s followers into reviving the United Irishmen call for self-determination and Catholic and Protestant unity under an Irish identity through armed rebellion. The Young Ireland movement broke away from O’Connell’s legislative movement and began to hesitatingly argue for armed insurrection and the establishment of an independent Ireland.

On July 29, 1848 the Young Irelanders made

a half-hearted attempt to launch their uprising.

It ended up being confined to a remote

farmhouse in Ballingarry belonging to a widow by the name of Mary

McCormack.

There a small mob of rebels besieged a

smaller party of Irish constables for several hours.

When the siege was relieved by the arrival

of police reinforcements, two of the besiegers had been killed and

several wounded.

The Young Ireland Revolt of 1848 or the

Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch, depending upon from which

political spectrum one observes the event, was over as soon as it began.

But several of the Young Ireland fugitives

who participated in the incident would become instrumental in the

founding of the Fenians ten years later by making the 1848 Rebellion

more important as a symbol in the future than anything it might have

achieved in its own time.

On July 29, 1848 the Young Irelanders made

a half-hearted attempt to launch their uprising.

It ended up being confined to a remote

farmhouse in Ballingarry belonging to a widow by the name of Mary

McCormack.

There a small mob of rebels besieged a

smaller party of Irish constables for several hours.

When the siege was relieved by the arrival

of police reinforcements, two of the besiegers had been killed and

several wounded.

The Young Ireland Revolt of 1848 or the

Battle of Widow McCormack’s Cabbage Patch, depending upon from which

political spectrum one observes the event, was over as soon as it began.

But several of the Young Ireland fugitives

who participated in the incident would become instrumental in the

founding of the Fenians ten years later by making the 1848 Rebellion

more important as a symbol in the future than anything it might have

achieved in its own time.

The Young Irelander James Stephens was twenty-four when he managed to escape from Ireland and arrive in Paris as a refugee. Only fragments are known about Stephen’s pre-Fenian life. His educational background is unknown but it was said he was employed on the Waterford and Limerick Railway as a civil engineer.[7] His most recent biographer, Marta Ramón was unable to find any surviving employment records from the railway but has established that before 1848 he was employed as a clerk at an auction house and bookseller.[8] Once safely in Paris, Stephens eked out a miserable living as a language teacher and freelance journalist, translating English press into French, while at the same time rising to prominence in the Irish exile community as a pamphleteer on Irish independence and a Young Ireland spokesman.

Stephens was joined in Paris

by thirty-two year old John O’Mahony, another fugitive of the 1848

revolt.

O’Mahony studied at Trinity College in

Dublin, although he never took his degree.

He was part of O’Connell’s Repeal movement

before seceding to the Young Irelanders in 1845.

In Paris, Stephens and O’Mahony lodged

together and would form a partnership—although sometimes strained—that

would last until O’Mahony’s death in 1877.

Stephens was joined in Paris

by thirty-two year old John O’Mahony, another fugitive of the 1848

revolt.

O’Mahony studied at Trinity College in

Dublin, although he never took his degree.

He was part of O’Connell’s Repeal movement

before seceding to the Young Irelanders in 1845.

In Paris, Stephens and O’Mahony lodged

together and would form a partnership—although sometimes strained—that

would last until O’Mahony’s death in 1877.

In Paris, Stephens and O’Mahony were caught up in Louis Napoleon’s overthrow of the Second Republic in December 1851 and are alleged to have participated in the street fighting in the failed defence of the republic. It was in this period of his exile that James Stephens was transformed from rebel to professional revolutionary.

Paris in this period was ground-zero of a myriad of revolutionary secret societies, some domestic, others in exile from other regions. Their quasi-Masonic pyramidal insulated cell-like structure would resemble later that of the IRB and Fenian “circles.” It was alleged that Stephens and O’Mahony were initiated into one of these secret societies: Louis Auguste Blanqui’s revolutionary Society of the Seasons, being the most often cited candidate.[9]

Stephens himself denied membership in any of the European societies but did write

Once I resolved that armed revolution was the only course for Ireland, I commenced a particular study of Continental secret societies, and in particular those which had ramifications in Italy….I proposed, however, not so much to make a slavish imitation of any known secret society as a selection of the good qualities of each, and fuse them into that which I was then about creating.[10]

The Carbonari of course would be the society that had the most “ramification” in Italy and its organizational structure would be similar to the one Stephens would lead in Ireland. If Stephens was not an initiate of any society, he did have links with members of these societies. In Paris, Stephens was tutored in Italian by General Guglielmo Pepe, the Carbonari deputy of Daniel Manin—the 1848 Venetian revolutionary. Stephens was also associated with Jérôme-Adolphe Blanqui—the brother of Louis-August of the Society of Seasons.[11]

John Rutherford in his Secret History of the Fenian Conspiracy published in 1877, claims that Stephens and O’Mahony were agents of the Russian secret service recruited to create chaos in the British Empire during the Crimean War. According to Rutherford, O’Mahony was specifically to organize an American branch of an Irish terrorist organization while Stephens was to organize the Irish branch.[12] Such a claim certainly might not be all that outlandish in the Cold War second half of the 20th Century. The timing of O’Mahony’s departure from Paris in December 1853 and his arrival in the USA in January 1854 coincides with the escalation of the Crimean War.

O’Mahony established himself in New York City and with several other prominent Irish exiles formed the Emmet Monument Association (EMA)—a veiled reference to his epitaph speech about no memorials being raised in his name until Ireland is free. The EMA’s objective was to raise a guerrilla army in the United States and send it into action in Ireland while England was bogged down in the Crimean conflict. At meetings in the Russian Consulate in New York and at its Embassy in Washington, the EMA was promised financial and material support by the Russians. But in the end, the support apparently never materialized.[13] That probably was the extent of the Russians’ hand in the founding of the IRB. The founders of the EMA could barely get along with each other let alone serve as agents of the Russian secret service.

In June 1855, Joseph Danieffe, a young tailor’s cutter in New York and a member of the EMA was given the mission of organizing a branch in Ireland and told that an armed expedition would follow him to Ireland in September.[14] Upon his arrival in Ireland, Danieffe proceeded to link-up with the various revolutionaries of the ’48 and ’49 rebellions and recruited them into the EMA with stories of the wealth of available support from the Irish in the US. But by September the promised expedition had not arrived and Danieffe hearing no further information from the EMA concluded that his mission was over and prepared to return to New York. In New York, the EMA was collapsing under the weight of internal conflicts among its leaders and intrigues with other rival nationalist movements—all competing in their attempts to raise financing among the Irish diaspora for their respective causes. Danieffe was persuaded to remain in Ireland for awhile longer until things get sorted out.

James Stephens in the meantime by the middle of 1855 abandoned Paris and began his journey back to Ireland via England. He arrived in Ireland sometime in January 1856. Again, it is unclear what his precise objective was—revolutionary or literary. Stephens and his followers claim he came to Ireland to organize the very revolutionary movement he would come to lead. But there is more evidence that what in fact drove Stephens at the time was the relentless poverty he was mired in as a refugee in Paris. He might have returned home in search of better literary and journalistic opportunities.[15] Whatever his purpose, Stephens began a famous ‘3000 mile’ trek through Ireland calling on old contacts in the revolutionary movement and making new ones. Back in New York, in the wake of the EMA’s collapse, the scholarly O’Mahony settled down into a literary project of his own—the translation of Geoffrey Keating’s History of Ireland from Gaelic into English.[16]

The consolidation of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and its American counterpart the Fenian Brotherhood is frequently linked to the massive public national campaign among the Irish in the USA in 1861 to raise money to repatriate to Ireland the body of a minor 1848 uprising exile who died in San Francisco—Terence McManus. The funding drive for the internment of McManus in his native soil was said to have re-wakened the nationalist fervour of millions of Irish Americans who generously contributed to the fund. [17] When McManus’ body arrived in Ireland it is said to have done the same there—the funeral procession it was claimed was seven miles long.[18] The McManus funeral is sometime cited as the cementing of what were said to be two independent movements—the IRB in Ireland and the Fenians in the USA.

This above described twinning of the IRB and the Fenians, however, was actually triggered four years earlier in 1857 by another funeral, that of an even more obscure veteran of the just as an obscure ‘49 uprising: Philip Gray. What troubled many of the Irish militants—including Stephens—was that the Irish press had entirely ignored Gray’s passing and mention of the rebellions. An attempt was made to raise money for a monument for Gray to memorialize the cause, but without press coverage of his death, this was unlikely to be a successful endeavour. This might have been the elusive ‘big-bang’ in the history of the Fenian movement. In March 1857 Stephens wrote to his fellow Paris exile O’Mahony in the United States broaching the idea of a launching a Gray monument fund there.[19] Stephens asked O’Mahony to raise funding on “your side of the water.”[20] The Gray Fund went nowhere but Stephens and O’Mahony established now an operative link. The remnants of the EMA in New York recognized in Stephens a viable contact in Ireland of much more mature revolutionary pedigree than the young tailor’s cutter Joseph Danieffe.

In December 1857 an emissary from New York brought Stephens letters from O’Mahony and other prominent US Irish militants offering financial support and an army if he would organize its reception and deployment in Ireland. In January 1858 Stephens sent for Danieffe and after reading to him the letters from New York (their text has not survived) he took command of Danieffe, ordering him to immediately return to New York bearing his reply.[21]

Stephens’ conditions were financially modest—three monthly instalments of £80 to £100 and absolute unquestioned authority over the operation—he demanded to be “perfectly unshackled; in other words, a provisional dictator. On this point I can conscientiously concede nothing. That I should not be hampered by wavering or imbecile it will be well to make out this in proper form, with the signature of every influential Irishmen of our union.”

In return Stephens promised to organize “at least 10,000 of whom 1,500 shall have firearms and the remainder pikes.” He concluded with the suggestion that the Americans send “500 men unarmed to England, there to meet an agent who should furnish each of them with an Enfield rifle.” Danieffe was to return with their reply and the money. The letter was dated “Paris, January 1866” perhaps some veiled message to O’Mahony referring to their shared time there in exile.[22]

Three months later Danieffe returned from New York.

On St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1858 he delivered to Stephens in Dublin the minimum £80 he had demanded and a document dated February 28 and signed by O’Mahony and fifteen other prominent Irish militants in the USA stating

We the undersigned members of the Irish Revolutionary committee, hereby appoint and constitute James Stephens, of the city of Dublin, Chief Executive of the Irish Revolutionary movement and give him on our own and our comrades’ behalf supreme control and absolute authority over that movement in Ireland.[23]

That evening, in Stephens’ Lombard Street lodgings a small group of Irish militants came over, read the letter and swore an oath founding the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood which was later renamed as the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB).[24] The next morning they departed in separate directions each to organize an IRB cell—or “circle” as they would be called.

In New York City in the meantime, O’Mahony who had came across the term in Keating’s History of Ireland when translating it into English, named his American branch of the IRB, the “Fenian Brotherhood (FB)” somewhere between January and April 1859.[26]

The American Fenian Brotherhood took its name from pre-Christian Third Century A.D. Gaelic warrior clans, the Fiana, or Fianna Eirionn. The Fians, Fiana, or Fenians according to one source “employed their time alternately in war, the chase, and the cultivation of poetry.” Their tradition also encompasses Scotland where their mythical chief—Finn or Fionn MacCumhal [Fion Mac Coohal], (the Fingal of Macpherson) is alleged to have died in A.D. 283.[27] The legendary origins of the Fianna were already being hotly debated in the 1860s as evidenced by a letter-writer to the Irish Canadian in 1866 who protested, “there were Fenians in Ireland before Trean Mor, the grandfather of Fion was born.”[28] In a more recent and less mythological dimension, the roots of Fenianism go back to groups like the Whiteboys and Defenders: peasant self-defence associations similar to the early Sicilian rural mafia and to their further transformation in the ‘post-United Irishmen-pre-famine’ Ribbonmen period into a transnational Irish nationalist underground.[29]

Whether the Fenians were nationalists, rebels, patriots, assassins, insurgents, bandits, irregulars, freedom fighters, pirates, murderers, martyrs, tribal militia, national revolutionaries, guerrillas or terrorists, depends much upon their historical chronology and an observer’s point-of-view. The Fenians were the first modern transcontinental national insurgent group in the western world with operational cells in Ireland, England, Canada, United States, South America, New Zealand and Australia and a banking centre in Paris. They organized themselves into cells called ‘circles.’ A Fenian circle was like a regiment: a colonel, the ‘centre’ or ‘A’ recruited nine ‘B’s or captains, who recruited ‘C’s or sergeants who each chose nine ‘D’s—the rank and file privates. Outside of the United States in the British Empire, Fenian circles operated clandestinely. A chain of secrecy worked its way upwards: the ‘A’ was known only to his ‘B’s, the ‘B’s only to their ‘C’s and so forth. Senior leaders in a city, territory or state were called ‘head centres.’[30] In Toronto and Montreal they infiltrated the leadership of a local militant Irish Catholic anti-Orange Order self-defence movement, the Hibernian Benevolent Society (HBS).[31]

Steam power gave the Fenians an unprecedented trans-Atlantic mobility; the telegraph linked them together at near internet speed (albeit without its bandwidth); cheap newsprint and steam driven printing presses gave them a mass-media voice; industrialism, an ocean of patriotic small wage earners to fund their cause; and the ascent of global capitalism offered a modern banking system to raise and distribute operational funds across oceans and continents, while the American Civil War would mobilize, arm and militarize tens of thousands of Irish-American patriots.[32]

While the early Fenians were not as bloodthirsty as today’s international terrorists, and as some of their many defenders point out, they were liberal-democratic-nationalist revolutionaries who strongly opposed clerical interference, and in the early stages of their history before resorting to kidnapping and dynamite bombings, believed in the concept of ‘open and manly warfare’[33] it can be nonetheless said that in the perception of authorities, the majority of the press and the public, the Fenians were regarded in their time in the way al-Qaida is perceived today.

The Fenians were broadly seen in the mid-Victorian era as a fanatical religious terrorist movement representing a radical fundamentalist Catholicism linked to a Papacy with political ambitions at its conspiratorial centre in Rome. Very similar to the way Muslim immigrant communities are suspected of sympathizing with and supporting and harbouring fanatical Islamic terrorists today, the Irish-Catholic immigrant community dramatically enlarged in Canada by famine migration in the preceding years, was suspected in the 1860s of Fenian allegiances. The clandestine relationship between the Catholic HBS in Canada and Fenians did not help although in the end, no Canadian Fenian circles are known to have participated in the June 1866 attack into Canada. Their presence in Canada contributed to the paranoia of a ‘fifth column’ but it never manifested itself in reality once the invasion occurred. The broader truth, however, was that Fenianism went beyond the question of religious sectarianism: of the 58 Fenians captured on the Niagara Frontier in 1866 and confined to the Toronto gaol, a full third were Protestants (19 Protestants with one prisoner claiming no religious affiliation.)[35] Fenianism was a nationalist republican movement and not a Catholic one.

Nonetheless, even when fighting in conventional uniformed formations the Fenians were classified as illegal combatants, piratical insurgents fighting a ‘dirty war.’ Familiar to international terrorism today but entirely new in the emerging telegraph networked world of the mid-nineteenth century was the Fenians’ global reach, their quasi-independent franchise cell-like structure, their operational reliance on long distance encrypted communications, use of public and press wire announcements, rallies and ‘fairs’, the launching of deceptive feints and disinformation, auxiliary cultural, educational and recreational programs, organizations and publications, use of long-term sustained intelligence gathering, deployment of “sleepers”, public and clandestine fund raising, the use of sophisticated financial instruments in the international banking system, and the complexity of the repercussions their acts had on international relations and the dimension of the alarm and fear they raised in the British Empire. The Fenians were the great perceived modern transnational internal threat in the British Empire in the second half of the nineteenth century until supplanted by first the fear of international anarchism followed by that of Imperial German spies. Despite these structural similarities to current terrorist movements, however, there is nothing in this thesis describing the conduct of the Fenian invaders in 1866 towards the civilian population in Canada or towards its officials, combatants and prisoners-of-war and wounded that could be characterized other than gallant and civilized; at least as gallant as an expropriating, foraging insurgent army can afford to be in battle.[36]

SOURCES:

[1] William D’Arcy, The Fenian Movement in the United States: 1858-1886, Washington D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 1947. pp. 229-230; M.W. Burns, “To the Officers and Soldiers of the Irish Republican Army in Buffalo”, June 14, 1866 in Captain Macdonald, p. 93

[2] In academic literature the IRB movement is sometimes referred to as “fenian” without capitalization while the capitalized “Fenians” refers exclusively to the U.S.-based movement.

[3] See: R.F. Foster, Modern Ireland 1600-1972, London: Penguin Books, 1989; Robert Kee, Ireland: A History, London: Abacus, 1991; Brian Jenkins, Era of Emancipation: British Government of Ireland 1812-1830, Kingston-Montreal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1988; David R. C. Hudson, The Ireland We Made, Akron, OH: University of Akron Press, 2003; Mary Frances Cusack, History of Ireland From AD400 to 1800, (1888), London: Senate Books Edition, 1995; Thomas Pakenham, The Year of Liberty: The Great Irish Rebellion of 1798, London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1997; Sean Cronin, Irish Nationalism: A History of its Roots and Ideology, Dublin: Academy Press, 1980; James S. Donnelly, The Great Irish Potato Famine, London: Sutton Publishing, 2001 and D.J. Hickey & J.E. Doherty, A new Dictionary of Irish History: From 1800, Dublin: Gill & MacMillan, 2003; Tom Garvin, “Defenders, Ribbonmen and Others: Underground Political Networks in Pre-Famine Ireland, Past and Present, No. 96 (Aug., 1982), p. 136; Oliver Rafferty, The Church, the State and the Fenian Threat, 1861-75, New York: St Martin's Press, 1999; Mike Cronin and Daryl Adair, The Wearing of the Green: A History of St. Patrick’s Day, London: Routledge, 2002; Kenneth Moss “St. Patrick’s Day Celebrations and the Formation of Irish-American Identity,1845-1875,” Journal of Social History, Vol. 29, No. 1. (Autumn, 1995), pp. 125-148; Michael Cottrell, “St. Patrick’s Day Parades in Nineteenth-Century Toronto: A Study of Immigrant Adjustment and Elite Control,” Histoire social/Social History, No. 49, 1992. pp. 57-73

[4] Tom Garvin, “Defenders, Ribbonmen and Others: Underground Political Networks in Pre-Famine Ireland, Past and Present, No. 96 (Aug., 1982), p. 136

[5] Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, London & New York: 1904. Quoted in Garvin, p. 136; John Matthew Barlow, Fear and Loathing in Saint-Sylvestre: The Corrigan Murder Case, 1855-58, Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 1998, pp. 25-38

[6] Kee, p. 201; Foster, pp. 323-324

[7] Anonymous, A Life of James Stephens: Chief Organizer of the Irish Republic, New York: Carleton, 1866. p. 27

[8] Marta Ramón, A Provisional Dictator: James Stephens and the Fenian Movement, Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2007. p. 26

[9] Ramón, p. 59

[10] James Stephens, ‘Personal recollections of ’48, a collection of press cuttings’, 1882-83, Notes on a 3,000 miles’ walk through Ireland, National Library of Ireland. Chapter 1. (Quoted in Ramón.)

[11] Ramón, p. 60

[12] John Rutherford, The Secret History of the Fenian Conspiracy: Its Origins, Objects & Ramifications, Volume 1, London: C. Keegan Paul & Co., 1877. p. 53

[13]

Danieffe, pp. vii-ix; D’Arcy,

pp. 5-7; Padraic Cummins Kennedy,

Political Policing in the

Liberal Age:

Britain’s Response to the Fenian Movement 1858-1868, PhD

dissertation, Saint Louis, Missouri: Washington University,

1996. p. 40

[14] Danieffe, p. 3

[15] Ramón, pp. 68-69

[16] D’Arcy, p. 10

[17] D’Arcy, pp. 18-20

[18] Danieffe, p. 70

[19] Ramón, pp. 70-71

[20] Stephens to O’Mahony, circa. March 1857; Fenian Papers Catholic University of America, Washington D.C., Fenian Collection: www.aladin/wrlc.org/gsdl/collect/fenian.shtml

[21] Ramón p. 73; Danieffe, p. 15; R.V. Comerford, The Fenians in Context: Irish Politics and Society 1848-82, Dublin: Wolfhound Press, 1985. p. 46

[22] See full text of letter in Appendix in Danieffe, pp. 159-160

[23] Michael Davitt Papers, Trinity College Dublin, MS 9659d/207, quoted in Ramón, p. 75.

[24] Leon Ó Broin, Fenian Fever: An Anglo-American Dilemma, New York: New York University Press, 1971. p. 1

[26]

D’Arcy p. 14 n.

[27] W.S. Neidhardt, Fenianism in North America, University Park and London: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1975. p. 7; Alexander Somerville, Narrative of the Fenian Invasion of Canada, Hamilton, ON: Joseph Lyght, 1866 p. iii

[28] Irish Canadian, February 14, 1866. The author, “Oisin” also protested, “the insinuation about excess drinking, in particular, I unqualifiedly pronounce false, and challenge the most inveterate enemy of the Irish race to produce an instance of intoxication referred to in any Irish manuscript relations to the Fenians. Conan Maol, or Bald, was the only man amongst that body who was over-fond of eating; but I never read of him being drunk.”

[29] Tom Garvin, “Defenders, Ribbonmen and Others: Underground Political Networks in Pre-Famine Ireland, Past and Present, No. 96 (Aug., 1982), p. 136; Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, London & New York: 1904, cited in Garvin, p. 136; For transplantation of Ribbonmen to Canada, see: John Matthew Barlow, Fear and Loathing in Saint-Sylvestre: The Corrigan Murder Case, 1855-58, Master’s Thesis, Simon Fraser University, 1998, pp. 25-38

[30]

D’Arcy, p. 55 n.

[31] Clarke, Brian P. Piety and Nationalism: Lay Voluntary Associations and the Creation of an Irish-Catholic Community in Toronto, 1850-1895, Montreal-Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993 for an extensive history of the HBS, also: Stacey, Charles P. “A Fenian Interlude: The Story of Michael Murphy,” Canadian Historical Review, 5 (1934), 133-154; W. S. Neidhardt, Michael Murphy, DCB; D’Arcy, p. 202, n.58, citing Donahoe’s Magazine, December 1879, p. 539; Peter M. Toner, “The ‘Green Ghost’: Canada’s Fenians and the Raids,” Eire-Ireland, vol 16 (1981), p. 29 cites, Phoenix, New York, 24 March 1866; Burton [P.C. Nolan] to McMicken, December 31, 1865, MG26 A, Volume 236, p. 103110-103113 [Reel C1662], Library and Archivies of Canada (LAC)

[32] For example of international money transfers and Fenian bond sales in France, see: Mitchel to O’Mahony, March 10, 1866, in Joseph Denieffe, A Personal Narrative of the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood, New York: Gael Publishing, 1906. p. 219; D’Arcy, p.82-84

[33] Mark McGowan to Peter Wronski, e-mail, February 3, 2010; David Wilson to Peter Wronski, e-mail, March 2, 2010

[35] Police Department of the City of Toronto, Description of Fenian Prisoners, 9 June 1866, Department of Justice, Numbered Central Registry Files, RG-13-A2, vol. 15, LAC.

[36] Even the Fenians’ enemy, George T. Denison, came to the same conclusion: Denison, The Fenian Raid, p. 63-64; also quoted in Somerville, p. 114